The Great White Hope: Can Hopelessness and Drug Abuse in White Communities Change the Drug War?

- Points Editors

- Feb 25, 2016

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 29, 2023

“Cocaine is an epidemic now. White people are doing it.” – Richard Pryor

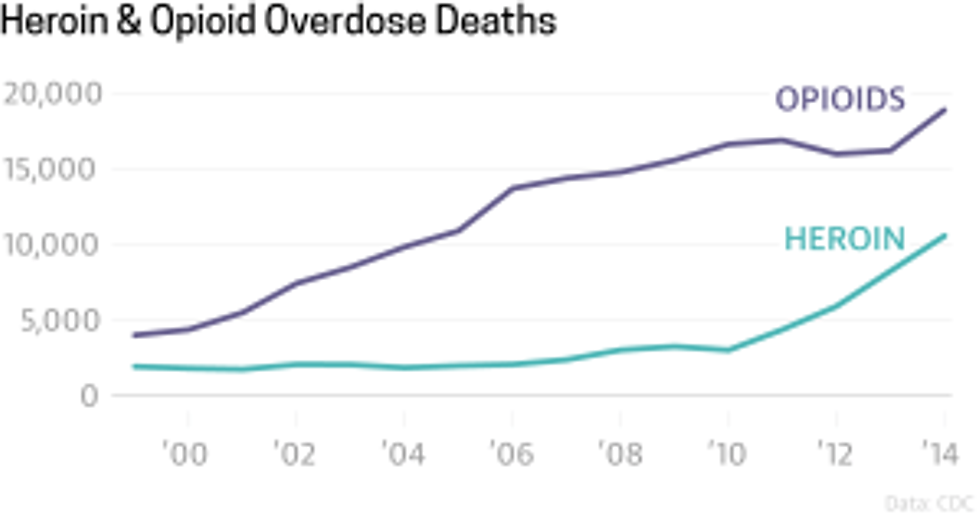

Heroin has a new face. The new face of heroin elicits more sympathy, compassion, and

Perhaps not surprisingly, the reason nonwhite populations have been less adversely effected by heroin’s rise is also steeped in racial prejudice. The history of medicine has long revealed the ways in which various nonwhite ailments have been ignored or

I first wrote about this trend in 2014, after the Governor of Vermont dedicated his State of the State Address to the heroin problem. As I argued then: Sound policy steeped in punishment—it turns out—makes much more sense when applied to 1970s Harlem rather than the land of maple syrup, autumn foliage, and good neighbors.

More recently in 2015, alarmist pieces citing increasing mortality rates among poorly educated whites ages 45 to 54 made their rounds. The rising death rates were chalked up to premature deaths due to suicide, drug abuse, and alcohol. Reports did not blame a lack of skills, personal responsibility, or the culture of Appalachia. The “Culture of Poverty” thesis and personal failings best apply to urban districts and their residents. Instead reports cited high levels of unemployment, low work force participation rates, and a creeping sense of hopelessness. One could make the same argument about young, nonwhite urbanites detached from the labor market in the years of heroin and crack. In fact, they did. In a 1988 New York Times op-ed, drug warrior Charles Rangel argued: “For too long we have ignored the root cause, failing to see the connection between drugs and hopelessness, helplessness and despair.”

When economist Angus Deaton explained the phenomena of increasing white mortality, he cited structures of the economy to explain the turn to drugs, alcohol, and suicide: “Those are the people who have really been hammered by the long-term economic malaise.” John Skinner, a professor of economics and medicine argued that having the “financial floor fall from underneath them” was disheartening and traumatic for whites ill-equipped to compete in an economy that had largely left industry and manufacturing behind. The same report also listed the increasing accessibility of opioids, and later, heroin as an explanatory factor. Might we apply the same argument to cities hobbled by deindustrialization and the rise of illegitimate labor via the drug trade in decades past? Instead policy makers and pundits blamed place, culture, family, community, and by extension, race.

Huntington, West Virginia has been especially hard hit, we’re told. Rather than declare war on citizens and demand more vigorous law enforcement, the Mayor of Huntington, Steven Williams has taken a different tact. Appealing for public sympathy, Williams explained the tragedy unfolding in his community to NPR: “What I’ve determined is that overdoses are more a symptom. The actual disease is hopelessness.” While his explanation mirrors that of Charles Rangel’s decades earlier, the conclusions and broader policy prescriptions that followed are virtually antithetical. Instead of calling

In Upstate New York, where I currently reside, heroin has also become an increasingly salient concern. Here too it is difficult not to notice the new, more humane, compassionate approach. The Mayor of Ithaca, Svante Myrick, the son of an addict, has proposed the nation’s first safe injection site. HOPENY, a New York State government organization has undertaken a massive public awareness campaign putting a human face–and context–to addiction. The website banner reads: “Addiction can happen to

Tuesday night PBS aired a Frontline special entitled Chasing Heroin. Advertisements for the two hour special previewed the “new face of heroin” and the subsequent “new war on drugs.” The profile of four white users did similar cultural work to the HOPENY testimonials. It humanized drugs users and drug addiction. Mayor of Bremerton, Washington Patty Lent was stunned when she started receiving phone calls about municipal bathrooms clogged with used syringes. In response, Lent proposed a methadone maintenance clinic. A local business owner, and former opponent of the clinic changed his tune midstream when he discovered his son too had fallen to heroin addiction. Unfortunately, many human beings fail to view addicts as human beings deserving of compassion until those human beings are their own.

Most interestingly, the special also highlighted a Seattle law enforcement initiative called LEAD, Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion. Summarily different from drug courts that are all too coercive, LEAD effectively affords officers the discretion to decriminalize heroin on a case by case basis. The overarching goal of LEAD is to push towards treating addiction as something other than a crime. LEAD is not preoccupied with forcing addicts to get clean before they are ready, but rather, more interested in reducing harm, limiting addicts contact with police and ancillary crime, and advocating

“Hamsterdam” in The Wire, but with more infrastructure, resources, and the official approval of authorities. It should also be noted that viewers might be less stunned or horrified at LEAD versus “Hamsterdam”because of the different sets of users. To be clear, LEAD was not implemented until white addiction became prominent. Before that, Seattle PD spent plenty of time punishing drug users of a different ilk. While LEAD is undoubtedly a marker of progress, it reminds us that progress is not color-blind. To that effect, will the discretion of officers to decriminalize play out the same bias already implicit in the criminal justice system?

In a powerful op-ed, Law Professor Ekoh Yankah reminded readers of an important message that warrants refrain: “We do not have to wait until a problem has a white face to answer with humanity.”